The Long Letter

If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter

Grace Can Lead Us Home - Mental Health

Sections

- Back At It

- A Short History of Mental Illness

- Irrational Systems for Irrational People

- A Pragmatic Consideration

- A Closing Anecdote

Back At It

Now that our local politicians have passed the ordinance on encampment prohibition, I will be returning to finish my walk through of Grace Can Lead Us Home. This chapter touches on the difficult topic of mental health.

Nye opens this chapter with a situation that happened while he was being interviewed at The Center. While touring the patio where close to 100 people were conversing, all discussions were cut short when a chair was thrown at one of Nye's friends who worked at The Center. The chair was thrown by Max, who Nye would later learn was diagnosed bipolar with aggressive tendencies. Watching this drama play out, Nye was impressed with his friends ability to de-escalate the situation. Training he would later put into practice himself.

Later, the author would eventually become Max's case manager and learn of his history and behavior. In an attempt to line Max up with housing he qualified for, one step required them to verify his mental illness. The only problem being that Max was banned for life from the location he was diagnosed from for being aggressive.

Banned. For life. For being aggressive—a key facet of the diagnosis they themselves provided. He was restricted from getting mental health services for exhibiting the textbook signs of his mental illness. This experience, among many others, taught me the myriad ways our mental health system abandons those most in need of its services. Our system of care has glaring flaws, especially for the most vulnerable, which can cause and perpetuate homelessness. (p. 107)

This chapter discusses the details of terminology around mental health and the difficulty in our systems in getting help for those experiencing it.

Leading off with the broad term "mental health", Nye quotes the Canadian Mental Health Association:

“Mental health includes our emotions, feelings of connection to others, our thoughts and feelings, and being able to manage life’s highs and lows.” (p. 108)

Think of mental health as an umbrella under which sits both good mental health, mental illness, and severe mental illness. "Mental illness refers to any psychological condition of any severity". Furthermore, under mental illness, some rise to the level of being considered SMI: severe mental illness, under which would be considered conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

We all experience seasons when our mental health is better or worse, but not all of us experience a mental illness. Among those who do have a diagnosed mental illness, very few of those conditions—less than 6 percent—fall under the category of SMI. Mental health affects us all, but not all the same. (p. 109)

Understanding these distinctions is important for how this relates to homelessness. It also will reveal the wide array of treatments available depending on the severity of the problem. While great strides have been taken in regards to mental health in general, Nye is quick to point out how quantity and quality of care for SMIs has not changed very much at all.

Arguing that one size does not fit all, Nye finds the need for both broader mental health services and specific services geared toward SMIs. Balancing both of these commitments is important.

A Short History of Mental Illness

In discussing the history of how the US had previously dealt with mental illness, the author refers to the work of E. Fuller Torrey, stating:

Before 1960, mental illness was primarily addressed by large mental health institutions and asylums. At their height, these institutions housed over half a million people. Because of mounting stories of abuse as well as shifting public sentiment as a result of dramatizations like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, funding was obliterated for these types of institutions, and their patients were discharged. (p. 111)

and further:

The stated goal of deinstitutionalization was to shift the care of those with mental illness to community-based outpatient centers. Unfortunately, this crucial step never fully materialized. Politicians bickered about whose responsibility it was to fund them. Community mental health centers that did receive funding capitalized on the ambiguity of the requirement and had no intention of serving those with severe mental illness. Many of the patients discharged from these institutions had nowhere to go and wound up living on the streets. (p. 111)

All of this leads to this conclusion:

We dismantled a flawed system for a vulnerable population, but have yet to put anything that comes close to matching the need in its place. For anyone whose mental illness causes them to lose income and their supportive community, there are primarily two places one can expect to end up: the streets or jail. (p. 111)

Nye points out that while 6 percent of Americans suffer from SMIs, that representation in the homeless population is 20-25 percent and 15-20 percent of those incarcerated.

We appear to have traded asylums for the revolving door of homelessness and jail.

Irrational Systems for Irrational People

This next section is probably the most frustrating one of this chapter. In it, Nye details how difficult and irrational obtaining services for those who are, well, difficult and irrational, can be. He opens this topic with some theological reflections on a young boy who is his possessed by a vicious demon in Mark 9. The disciples, being unable to cast out the said demon, call on Jesus who frees the boy and explains, "This kind can come out only through prayer".

Nye ponders, like many other Christians, whether this episode is capturing perhaps an ancient understanding of severe mental illness. Either way, the point he most associates with is in the helpless feeling that Jesus' disciples have in their inability to make the situation better.

Nye uses the example of Adam, a man who repeatedly turns down housing because he's under the mistaken delusion that he actually owns land and will be able to move there soon after some legal issues are corrected.

This of course, is not true at all. But for Adam, it is very much true. Nye continues:

Because of this, he has passed up multiple housing opportunities and a variety of long-term services—especially mental health services. “No, no, nothing like that, I don’t need that. I’m not like these other crazy people.” (p. 113)

The term for what Adam experiences is anosognosia. It’s a symptom most commonly associated with dementia, but it is extremely common with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as well. The term refers to a person’s inability to recognize that they have mental illness. The severity of this varies and can even change over time. Adam is by far the most severe case I’ve experienced. (p. 113)

Due to this particular issue, Adam finds himself unable to obtain help. Nye goes on to say:

For Adam to qualify for housing because of his mental health, he would be required to acknowledge the condition that his condition precludes him from acknowledging. If we were to pursue an alternate qualification for housing, he would be flagged in the process for stating that he owns property, regardless of the fact that this isn’t true. And so Adam remains stuck in a system that’s supposed to serve people exactly like him but is so incomprehensible that he can’t possibly navigate it. As with the disciples in Jesus’ story, it feels like the only thing I can do is pray. (pp. 113-114)

It's here that Nye finds a system just as difficult and irrational as the population it serves to help. It's no wonder that Nye most associates with the disciples' feeling of helplessness regarding the possessed boy.

The author continues by telling the story of Steven, a man who, it turns out suffers from schizophrenia. While working with Steven, Nye discovers that he is eligible for Social Security Disability (SSDI). The only problem: in order to remain on disability, Steven has to re-certify his disability every three years. Even though there is no known cure for schizophrenia! To make matters worse, the packet of information to understand this process is large, dense, and filled with technical jargon of which Nye needed the experience of more senior case workers to decipher. How would anyone expect Steven to navigate this process given his condition?!

I’m not quite cynical enough to believe that this system was designed for people to fail. But I must admit that if I were in charge of creating a system that was designed for failure, it would look a lot like the one we have. (p. 116)

This is just one of many examples you can easily find about our current mental health system and its processes.

A Pragmatic Consideration

While Nye isn't doe-eyed about the many serious issues that encumber our current services and processes, he doesn't give up here either. Stressing that since so much does fall under the umbrella of mental health and much of that has to do with community and relational issues, he stresses that there is still plenty for a person to do that is within their power.

Breaking down four elements that help others on their pathway to recovery from trauma, a healing relationship, safety, reconnection, and commonality, Nye stresses that while the larger issues may be out of a person's control, all of these points are more applicable on the relational level.

Bringing these ideas together in tandem with a housing-first model:

Under the old model, people had to demonstrate their “readiness” for housing by complying with a particular treatment plan, which often includes attending multiple appointments, managing medication, and numerous other hoops. Asking people to comply with treatment while vulnerable on the streets is not only entirely nonsensical, but also perpetuates trauma. Housing First, on the other hand, has proven incredibly effective at stabilizing people with severe trauma and mental illness. This should come as little surprise: people with a safe place to sleep at night and a place to store medications are in a much better position to seek and maintain treatment. (p. 119)

While many aren't in a position to address the structural issues our systems face, there is a lot the church can do that goes a ways toward promoting the improved health of the unhoused.

Creating a space where people can come, spend time, and connect with one another is an evidence-based practice for improved mental health and trauma recovery, both for unhoused folks and for the broader community. (p. 119)

In closing this chapter, the author discusses mental health and the church. The church hasn't exactly been a haven for those experiencing homelessness or mental health issues.

Churches ought to be supportive communities, unwaveringly hospitable and accessible to those with mental illness. Overall, however, this has not been the case. Faith communities have been historically dismissive and ignorant of and even hostile toward the topic of mental health. (p. 120)

Encouraging churches to consider how their services are structured and what sort of tolerance they have for those dealing with mental health issues, Nye asks churches to perhaps re-evaluate how they perceive mental health issues.

If we truly want to end homelessness, our theologies and our ecclesiologies need to be big enough to welcome people with severe mental illness to find acceptance and support in our churches. We need to become comfortable with the idea that there is no correlation between the amount of faith someone has and their mental health. However, there is a direct correlation between mental health and the amount of community support a person has. (p. 121)

A Closing Anecdote

Since I've started writing about my experience working with Gather, I've found that it has inspired others to share their stories with me as well as among others. When I discussed my struggle with depression, I was heartened to find out that others have experienced similar issues. We are not alone in these things. As more people open up about their experiences, it builds tiny pockets of community extending outward like expanding concentric circles.

So I wasn't surprised to find myself talking with a friend this week about their past struggle regarding mental illness. To respect her privacy, I'll be avoiding identifying details.

The beginning of her story starts around 2007. She's married with two young babies. In April, she begins to feel "off" and seeks out a counselor who dismisses her concerns and instead decides to counsel her on parenting.

She decides to seek out a new counselor, this time being told she's just a stressed out mom and is probably lacking sleep. (Literally describing every mother I've ever known)

It's in July that she finds herself having a manic episode, though at the time, she didn't have the words for it. She became angry and belligerent toward her husband and out of concern for how she was feeling called the cops. The cops show up and arrest her, even though she's the one who called them. They jail her for half a day, release her, and she is court ordered to do community service and take anger management classes. At no time is she evaluated for any mental health issues.

In October of that year, she begins hearing voices telling her to throw her kids down the stairs. Her kids are both under the age of 2 at this time. Concerned about her own thoughts, she calls her counselor. They advise her to call her husband to come home, which he does. Then the counselor tells her to have a good weekend and hangs up! Realizing this is a poor response, she calls her PCP who tells her to get to the ER immediately. Upon arriving at the ER, she's given a sedative and sent back home. Once again, at no time in the process, is she evaluated regarding any mental health concerns.

It's not until she discusses the ongoing issue with her probation officer that they manage to get her into a psychiatrist in November. It's here that she is diagnosed with bipolar type 1 with rapid cycling and hallucinations.

After all of this, she still has to endure the ongoing process of finding the right medication to treat her newly assessed bipolar disorder, which ends up being another months-long process.

I work in technology, specifically distributed systems. One of the biggest issues that I see in large systems is often in the hand-off between boundaries. It's in these gaps that responsibilities fail and failure states can arise. And often, teams don't know who should be responsible for monitoring or working issues that come in these spaces.

I can't help but feel so frustrated at the multiple failures in my friend's story. So many professionals, trained for this very purpose, or at least to be aware of it, not taking her concerns seriously or not following up after the fact. I can't even begin to express my exasperation at her attempts to call the police of her own accord and being arrested for it! Unexamined responses like this just further push issues like these around in a system completely devoid of context or intelligent processes.

If it takes this much effort for a person of their own recognizance to get the help they need, how much harder is it for those whose mental health issues preclude them from recognizing their own need for help?

When politicians focus their efforts on sweeps and prohibitions as a "good first step", I can't help but feel they are just contributing to the ongoing faceless bureaucracy so prevalent in the system already.

Perhaps that is why it is all the more important to encourage and develop a community of advocates and caretakers for those who have no such community. Churches of all places should be first and foremost havens of community and safety, and yet, in my experience, they have been just the opposite. What should serve as a hospital for the broken ends up functioning as a courtroom for the accused. May God judge us accordingly.

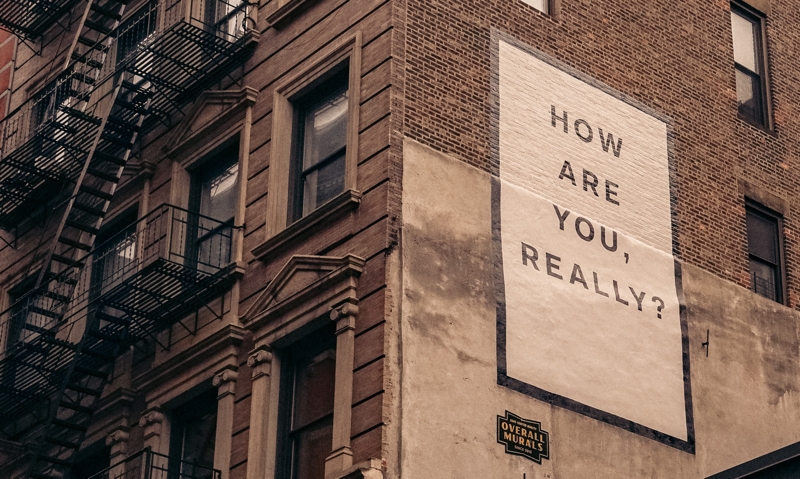

Photo by Finn on Unsplash