The Long Letter

If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter

Can We Criminalize Our Way Out Of Homelessness?

Sections

- Seeing results?

- A Questionable Cause

- Risk Factors for Homelessness

- Housing Availability and Affordability

- Politicians Digging Themselves Out Of A Hole

- Conclusion

Defenders of public safety and personal rights celebrated a small victory Monday evening when one local municipality successfully passed an ordinance banning camping on its public property, effectively criminalizing homelessness and thus ensuring the safety and well-being of the community who would rather not see those in the community who have neither safety nor well-being.

At the same time, the municipality next door was able to annex land where a problematic homeless encampment currently resides. The very same one of which I have written about many times before.

All of this follows nearly five months after Lewis County passed Ordinance 1338, prohibiting encampments on county land. It's been a banner few months, policy-wise, for our local politicians concerned about our ongoing homelessness problem.

Seeing results?

So let's check in on the results of all of this political policy maneuvering. What progress can we see regarding our homeless population? Can we assume, since its been nearly five months since Lewis County has passed it's ordinance that our local homeless population has been successfully relocated?

Well, the Blakeslee Junction encampment is still around. Which is to be expected given that it was never on county land to begin with even though it was a primary source of inspiration for the county ordinance.

In fact, lack of enforcement, to date, is mentioned in passing in the article detailing the recent annexation but not explained:

As for the Blakeslee Junction encampment, Pierson told the council at last month’s meeting the city is working on entering an interlocal agreement with Lewis County and other partners to address the ongoing issues there. Lewis County last fall passed local law banning homeless encampments on county land, though it has yet to be enforced.

Now this is telling. If one were to go back and listen to the rhetoric about the absolute necessity of passing the county ordinance immediately due to safety issues the encampment posed to the community, you would likely assume that action would soon be taken, right?

Aside from the most obvious issue, being that the encampment wasn't under county jurisdiction (at the time), there is another issue at play that effectively makes the county ordinance, and in the same way the Chehalis ordinance, effectively inert: lack of housing. At least in regards to criminalization.

You see, last year, the Ninth Circuit Court upheld and clarified the right that homeless persons have to survive in the absence of housing. You can imagine this was a devastating blow to those who did not feel that homeless persons had a right to survive in the absence of housing. In short, displacing a population by making it illegal to be homeless while there is no housing to be had is considered cruel and unusual punishment. Who knew?

So why all the sound and fury, signifying nothing (my apologies to Faulkner)?

For starters, I think it ultimately just feels good to do something. Even if it's inactionable at present. Even if it's a cart-before-the-horse sort of thing. More likely though, I would say that it probably isn't unrelated that the county ordinance just happened to fall in the sphere of public debate not long before election season and made a great rallying cry to square the political wagons so to speak. Stirring the pot has always been an effective strategy in political tribalism. In short, it's good for elections.

So we have two ordinances criminalizing camping on public land that are, at this time, unenforceable given the absence of housing. Though law enforcement can still get mighty creative when it comes to rousting the unhoused even without the ordinances in play.

We still only have the one shelter with limited capacity compared to the number of our unhoused population from five months ago. Worse, since then, we've had the closure of two local motels that have only exacerbated our lack of housing. Things are literally worse now than when all of this began.

The county is currently taking proposals for a night-by-night shelter that, in earlier comments, they had hoped to see available sometime this year. I'm hopeful for that effort. Though it's not a housing solution.

A Questionable Cause

As readers of my "letters" are likely aware, I'm no fan of criminalizing homelessness. There are various reasons for this which you can find in my previous writings on the matter. For this letter however, I want to address one very big issue I have with all of these efforts:

Pursuing the criminalization of homelessness as policy is criminalizing a symptom of an issue, not actually addressing the source or cause. Policies geared toward criminalizing homelessness are effectively reactionary and ineffective in actually addressing that which increases the risk of homelessness.

Our local politicians are spending a considerable amount of energy implementing policies to criminalize those who are unhoused. More so, the policies they've managed to pass can't legally be enforced until our lack of housing is addressed.

Might it be more productive to examine the issues that contribute to increased risk of homelessness for our population and perhaps implement policies around those items?

Risk Factors for Homelessness

As in most complicated systemic issues, the factors involved that increase the risk of homelessness for individuals and families are often interconnected and overlapping. There are known statistical indicators though:

- Housing - Availability of housing is one such factor that determines a person's risk for becoming homeless.

- Income - Low income populations will have a higher risk of becoming homelessness as the higher cost for housing limits their ability to pay for food, clothing, transportation and so on.

- Health - This is one area where factors become inextricably linked. Having health issues can increase the risk of homelessness as well as experiencing homelessness can have a disastrous impact on a person's health.

- Domestic Violence - Many victims of domestic violence are left with few choices when it comes to safety putting this population at a higher risk of homelessness.

- Race - It's well documented that minority groups make up a larger share of homeless populations.

You can read more about the causes of homelessness here and here but for purposes of this letter I'll focus on only two: housing availability and the affordability.

Housing Availability and Affordability

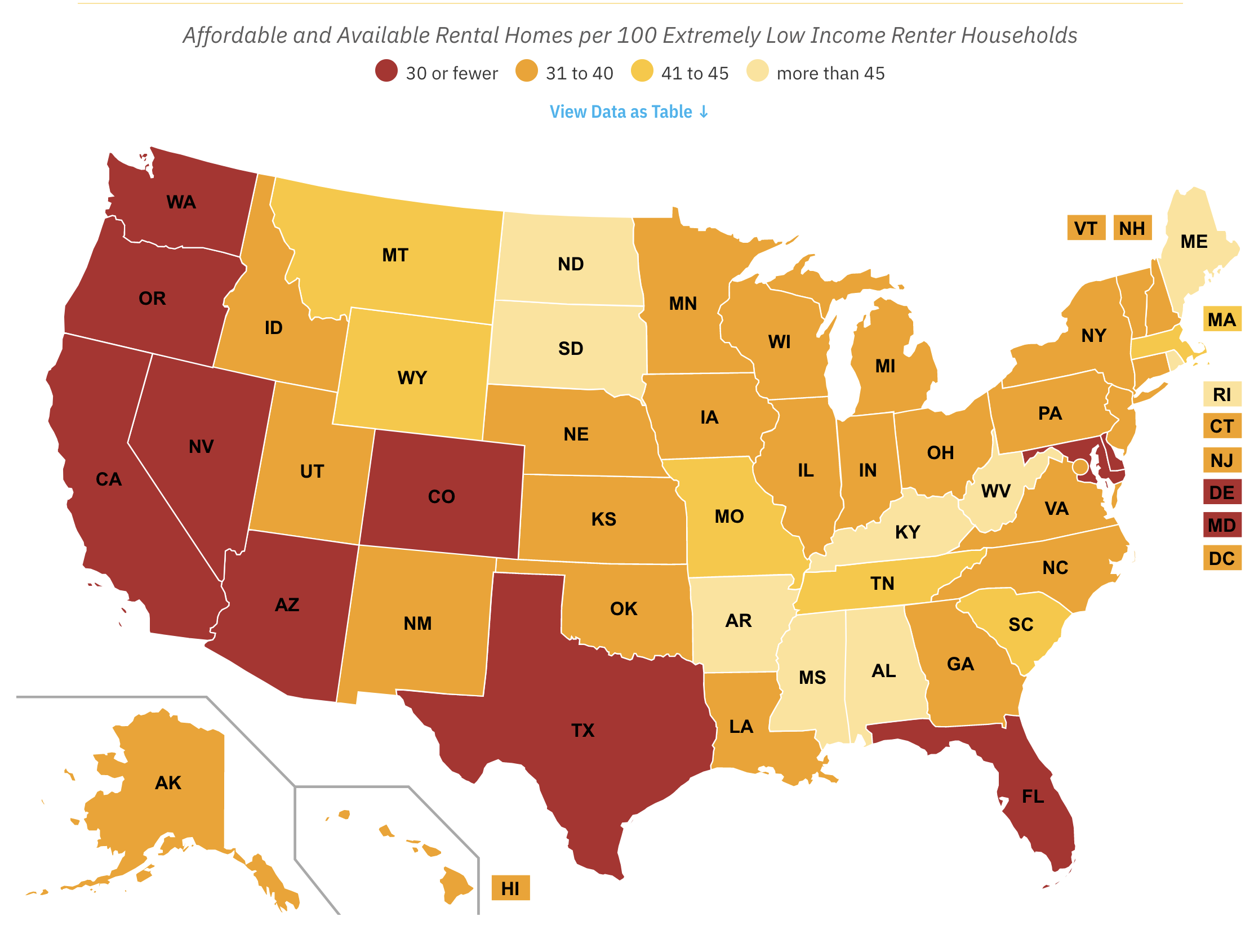

If you look at the graphic above (provided here), you can see our little state, Washington, is deep in the red. Meaning it has "30 or fewer affordable or available rental homes per 100 Extremely Low Income Renter Households"

The question this provokes is: what is an "Extremely Low Income Renter Household"? Well, that is understood using the metric of Area Median Income (AMI), which is the midpoint of an area's income distribution. This particular metric is used in reference to the affordability of housing in the same area.

If you need a refresher on mean, median, and mode, Khan Academy has a nice article on it here.

Now, I could go crunch all the numbers on that but thankfully HUD has done all the work for me, and included their steps so you can see how they came to that value. The Median Family Income for Lewis County, Washington is $79,200.

With that number, we can now narrow in on the three low-income tiers of AMI for Lewis County as provided by HUD here:

- Low Income (at or below 80% of AMI) - $63,100

- Very Low Income (at or below 50% of AMI) - $39,450

- Extremely Low Income (at or below 30% of AMI) - $27,750

So here's the name of the game: housing. That graph above states that Washington has 30 or fewer rental homes per 100 extremely low income renter households.

Translation: If we had 100 people that are defined as "Extremely Low Income", we only have enough affordable housing for 28 of them (according to recent data).

Now, I am sort of mixing numbers here as the AMI is defined by Lewis County compared to the housing market of the entirety of the state of Washington. Can I clarify our specific info more?

If I used the HUD calculator for Fair Market Rent, we might be able to get a better picture of how far a low-income AMI will get you in this area.

According to this data, the fair market rent for Lewis County as of 2023 is:

- One-bedroom: $902

- Two-bedroom: $1,143

In order to afford 1 bedroom rent and utilities, without paying more than 30% of your income, for Lewis County, you would need to have a monthly income of $3,006 or $36,080 annual income. As you can see, this would price out the "Extremely Low Income" and "Very Low Income" groups right off the bat as well as be near impossible for "Low Income" families. And remind you, this is for a ONE BEDROOM rental without other expenses like food, clothing, transportation, and so on.

Politicians Digging Themselves Out Of A Hole

Can you see now why I'm so skeptical of the criminalization of homelessness? How it's just swatting at symptoms and ignoring causes? Without affordable housing, more and more families and individuals risk becoming homeless going forward. We can increase the penalties for being homeless all we want but without addressing that actual issue at hand, we're at best failing and at worst making it harder for that population to find stable housing going forward.

I wonder what a person could find if they dug through past decisions of our local political representatives on issues of housing and affordability? I can think of two situations off the top of my head: one in which the Centralia City Council said some quiet parts out loud regarding provisional supportive housing and another where the Chehalis City Council weighed in on congregational housing. To my knowledge, the Centralia issue was resolved once they realized it wasn't their problem (which made it okay I guess?).

Still though, I have to wonder, given that housing is the name of the game here and it's also foundational to addressing more complicated issues such as substance abuse and mental health issues, I wonder what our track record has been over the last five or so years policy-wise?

When I think back to the Let's Talk About It interview between Richard DeBolt and Sean Swope and the dismissal of providing porta-potties and garbage services to at least mitigate the issue of the Blakeslee encampment, I can't help but feel it's something of a microcosm of what we see day in and day out: dismiss mitigation efforts as ineffective, campaign on the unmitigated situation, criminalize the symptoms, and then, when another political issue needs fire to rouse the base, use the local bullhorn to loudly disseminate low-effort uninformed opinion.

Conclusion

Our community can do better. We have an amazing community of resourceful people doing a lot of good work. The issues are complicated and difficult and may take a lot of time to work out. I think our time would be better spent finding creative solutions over criminalizing symptoms.